The Cartography of Fear: Masks as Boundaries in Ritual and Rebellion

The scent of aged wood and dried pigment clings to my memory, inextricably linked to the first time I truly understood the power of a mask. It wasn't in a museum display, illuminated and sterile, but in a dusty antique shop in rural Japan. A weathered Noh mask, a snarling demon called a

Masks, across cultures and centuries, are far more than simple representations of spirits or characters. They are potent symbols of boundaries: physical spaces demarcated as sacred, societal roles rigorously enforced, and, historically, camouflaged avenues for dissent and resistance. They are, in essence, a cartography of fear, of respect, and of rebellion, etched onto a single, expressive face.

Consider the elaborate masks of the Kwakwaka'wakw people of the Pacific Northwest. The towering, intricately carved masks, often representing mythical creatures like the Thunderbird or the Sisiutl, are not simply displayed; they are integral to the winter ceremonies, the

Similarly, in the vibrant dances of Bali, the Rangda, the demon queen, is brought to life through a terrifying mask. The Rangda is an embodiment of chaos and destruction, constantly battling the benevolent Garuda. The ritual is not merely entertainment; it’s a dramatic enactment of the cosmic struggle between good and evil, with the mask acting as a powerful focal point, defining the space and the roles within it. Those who dance as demons are separated, temporarily, from the everyday.

Beyond defining spiritual boundaries, masks often delineate social roles. In many African cultures, initiation ceremonies utilize masks to signify a young person's transition to adulthood. The mask isn't just a disguise; it’s a symbol of their new status, a visual declaration of their responsibilities and privileges within the community. The craftsmanship itself – the materials used, the complexity of the carving – often reflects the individual's social standing and the importance of their role. Antique masks from these ceremonies, often passed down through generations, offer glimpses into complex social structures and lineage. The traditions are remarkably similar to those surrounding the creation of Haitian masks, where Vodou and cultural expression intertwine.

I once handled a Dogon mask from Mali, a

The power of a mask lies not only in its ability to define; it also has the potential to subvert. Throughout history, masks have provided a crucial layer of anonymity for those seeking to challenge authority. During periods of oppression, masks allowed individuals to speak truth to power, to organize dissent, and to carry out acts of resistance without risking immediate reprisal.

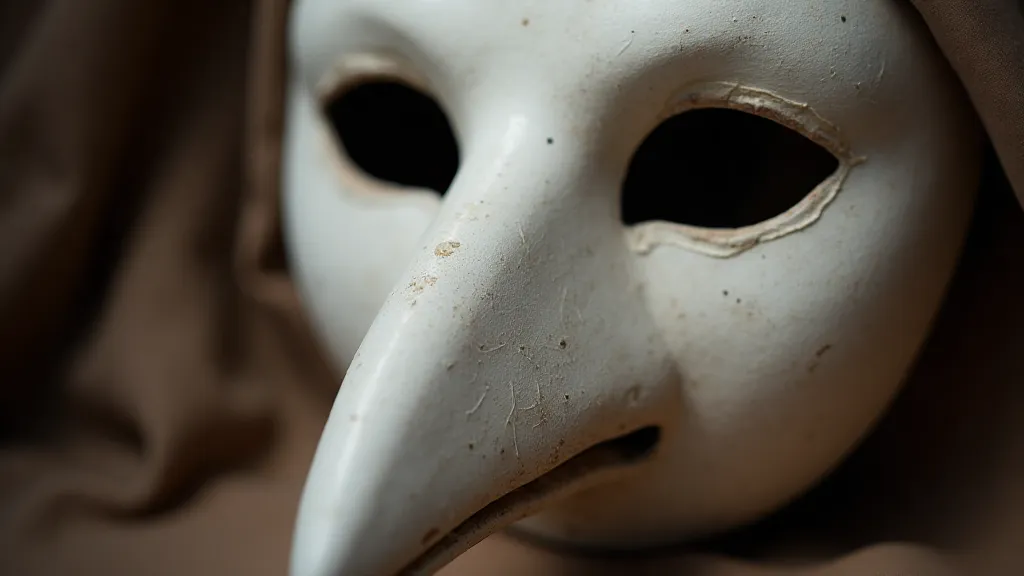

Think of the Venetian bauta mask, traditionally worn during the Carnival celebrations of Venice. Originally intended to allow commoners to disguise themselves from their social superiors and engage in revelry without fear of recognition, the bauta also became a symbol of political protest during the uprisings against the Venetian Republic. The anonymity afforded by the mask allowed for a temporary blurring of social lines, enabling the voices of the marginalized to be heard.

During the French Revolution, masks were worn by revolutionaries to avoid detection by the authorities, allowing them to gather in secret and plot against the monarchy. Similarly, in colonial contexts, indigenous populations used masks to maintain cultural practices forbidden by the ruling powers, safeguarding their traditions under the guise of anonymity. The cultural preservation achieved through masking shares a similar purpose to the storytelling found in the masks in Samoan Siva Samoa dance, where spirits and narratives are interwoven.

The creation of a mask is rarely a simple act of carving. It's a process steeped in tradition, requiring not only artistic skill but also a deep understanding of the cultural significance of the object. The choice of materials – the type of wood, the pigments used, the embellishments applied – all carry symbolic meaning. The dedication and skill required are comparable to the traditions behind the masks in the masks of Kerala, India, specifically in Kathakali and Theyyam traditions, where elaborate costumes and makeup transform performers.

Restoring antique masks is a delicate process, requiring a skilled hand and a reverence for the original craftsmanship. Overzealous cleaning can strip away layers of patina that have accumulated over time, diminishing the mask’s historical value. A true restoration focuses on stabilizing the object, repairing any damage, and preserving the original character of the mask.

Collecting masks is more than acquiring beautiful objects; it’s about preserving cultural heritage. Each mask tells a story, a window into a specific time and place. Responsible collectors prioritize provenance – knowing the history and origin of the mask – and support artisans who are committed to preserving traditional techniques. The responsibility of stewardship echoes the significance of masks used in ritual and performance across the world.

Returning to that